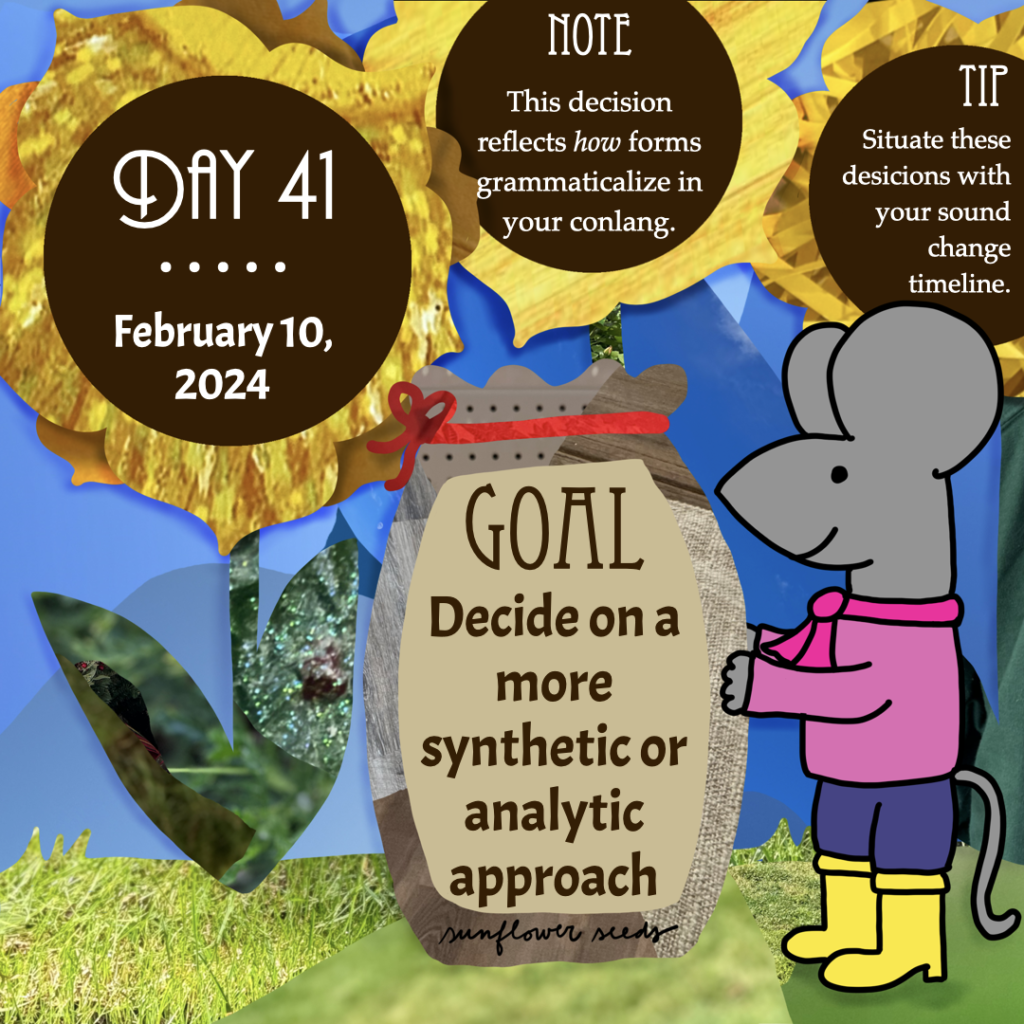

Goal: Decide on a more synthetic or analytic approach

Note: This decision reflects how forms grammaticalize in your conlang.

Tip: Situate these decisions with your sound change timeline.

Work focus: Learn/Brainstorm/Try

The way units come together in a language’s grammar can be more analytic or more synthetic. In a more analytic system, each unit is more likely to be its own word, whether it’s a content word carrying semantic meaning (like a noun or verb) or a function word encoding grammatical information (like an adposition, article, or tense marker).

The more synthetic a system is, the more likely units are to come together, such as having grammatical information encoded on affixes that attach to a noun or verb base. At an extreme end of the spectrum, the most synthetic languages build entire clauses around a single root, such as having a verb serve as the core root with all other elements affixed onto the verb.

While languages can fall into the extremes of this spectrum, the majority of languages fall in between, tending toward one side or another. In other words, many languages tend to be more analytic or more synthetic rather than being, for example, completely analytic.

Let’s look at a hypothetical example. This example will incorporate grammatical features we haven’t focused on yet, but they will serve to show the kinds of distinctions today’s decision can potentially effect on your language’s grammatical system. This language will be SVO and nominative-accusative, with the following lexical entries:

- be “past tense (occurs after the main verb)”

- molo “apple”

- nu “nominative case (occurs after the subject)”

- shau “to eat”

- tissa “child”

- zi “accusative case (occurs after the object)”

The goal is to put these units together to mean “The child ate the apple.” The units could come together in several ways:

- Fully analytic: Tissa nu shau be molo zi.

- More analytic: Tissa nu shaube molo zi.

- More synthetic: Tissanu shaube molozi.

- Fully synthetic: Tissanushaubemolozi.

The units themselves are not affected in the different examples—it’s how the units come together that changes. While this example uses the same phonological forms for demonstration purposes, your decision today will affect how the forms look and interact with other units in your language. For instance, forms that are affixes may undergo more phonological reduction and interact more with the bases they attach to than forms that are freestanding words.

If you want a more synthetic approach, you should consider when the forms come together in terms of the sound changes you selected. Are these early affixes that are affected by all sound changes? Are the forms reduced before the sound changes? Are they reduced during the sound change process? All these decisions will affect how the forms appear in their modern versions.