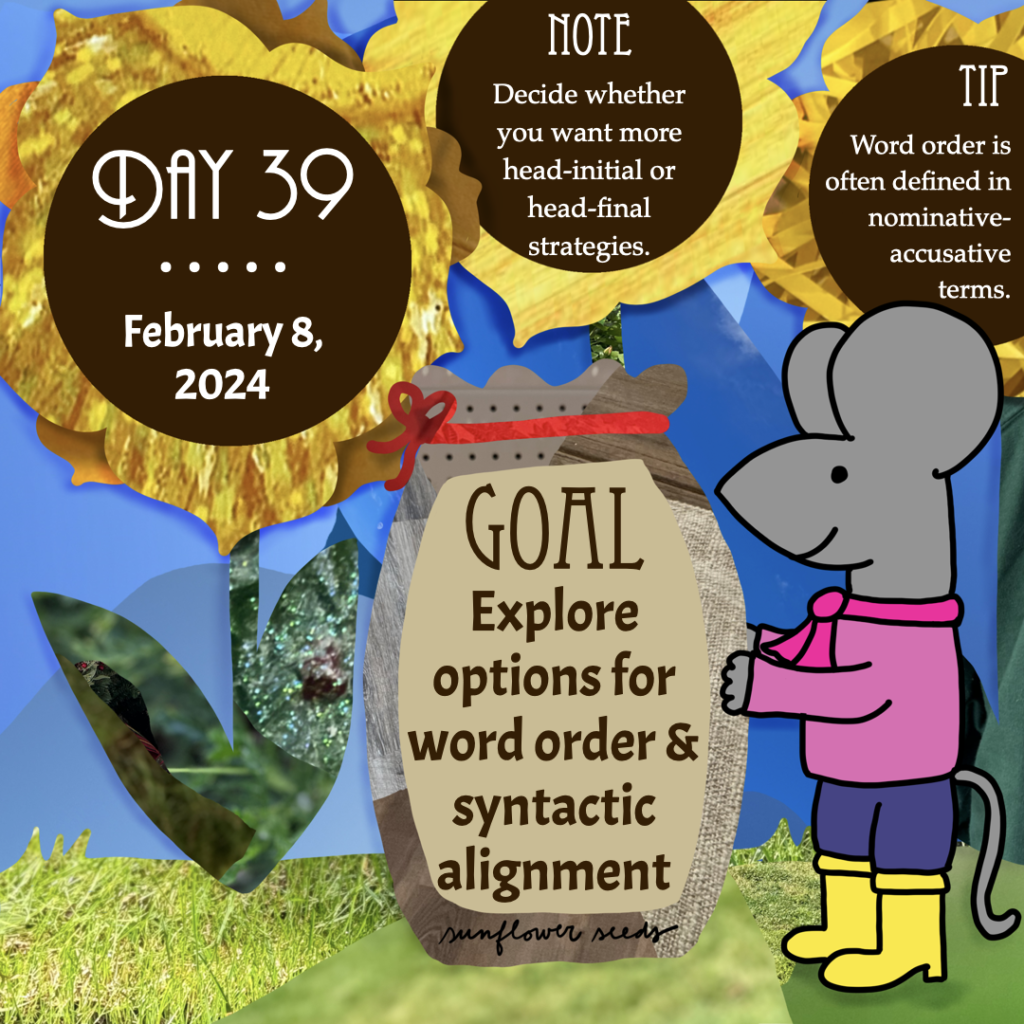

Goal: Explore options for word order and syntactic alignment

Note: Decide whether you want more head-initial or head-final strategies.

Tip: Word order is often defined in nominative-accusative terms.

Work focus: Learn/Brainstorm/Try

It’s time to move on to decisions about grammar! The first major decision I’m presenting to you is in two parts because these two features are so intertwined that you need to make them both at once. The features are word order and syntactic alignment.

Syntactic alignment refers to the way a language treats its major arguments in a clause. Some languages have a nominative-accusative alignment. In such a system, the subject is typically the agent (or the doer) of the verb and occurs in the nominative case, and the object is typically the patient of (or the argument most affected by) the verb and occurs in the accusative case. If a verb is intransitive (that is, it does not occur with a direct object), its subject still occurs in the nominative case. (You don’t need to decide yet if you’ll actually mark these cases in your language. That decision will come later as you build the grammatical features of your language.)

Another type of syntactic alignment is ergative-absolutive. In an ergative-absolutive system, the agent of a transitive verb occurs in the ergative case, and the patient occurs in the absolutive case. The subject of an intransitive verb occurs in the absolutive case. Notice that shift—the subject of an intransitive verb is considered a different kind of argument than the agent of a transitive verb in this kind of system.

If you have never heard of these alignments or the terms used to define them, you should spend today researching these features to explore what’s possible. If you are familiar with these systems, you might want to spend the day exploring other systems (e.g. tripartite marking) just to see what’s possible.

The syntactic alignment distinction is important to recognize because word order is defined in terms of S-V-O placement, where S is the subject, V is the verb, and O is the object. In other words, it’s defined using a transitive verb and using terminology associated with nominative-accusative alignment. If you end up selecting ergative-absolutive alignment, you might want to define word order in terms of A (for “agent”) and P (for “patient”) when describing how transitive verbs work.

Whatever you call the arguments, word order focuses on the basic ordering of elements when the clause is headed by a transitive verb, which means there are three constituents involved. Using the standard S-V-O notation, that means there are six different word orders possible:

- SOV

- SVO

- VSO

- VOS

- OSV

- OVS

The top three in this list are the most common: SOV, SVO, and VSO. Languages tend to prefer a basic order where the subject precedes the object.

When you select a word order for your language, you are also determining whether your language will likely be predominantly head-initial or head-final in its phrases because headedness is related to the verb’s position relative to the object. Phrases are named after their head word, so a verb phrase is headed by a verb and a noun phrase is headed by a noun. The head determines what else can (or must) occur alongside it inside the phrase, and it provides the most semantically salient information of the phrase.

Languages with the verb occurring before the object (i.e. SVO, VSO, VOS orders) tend to be more head-initial, and languages with the verb occurring after the object (i.e. SOV, OSV, OVS orders) tend to be more head-final. Headedness of your language will play a large role later in grammar construction.

In other words, take some time today to explore these options because they will have ramifications for your language further down the road.