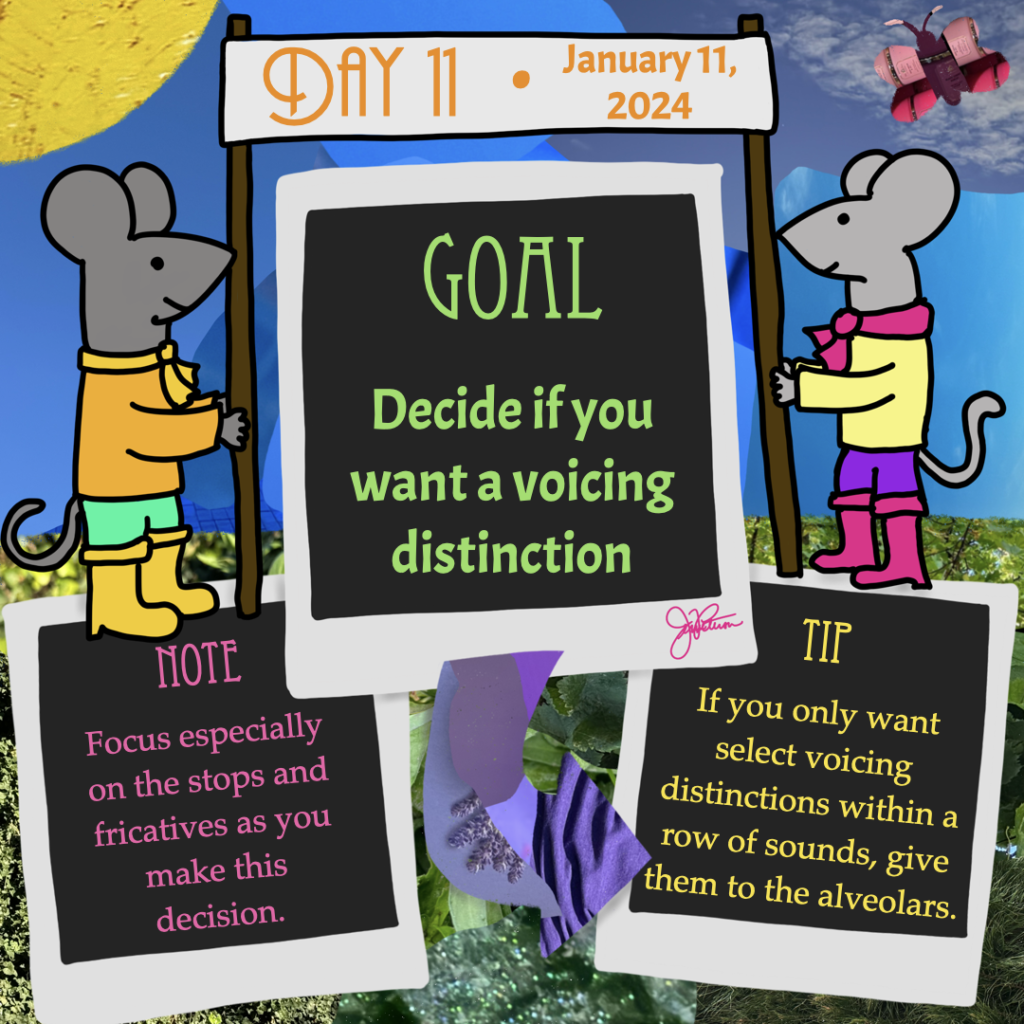

Goal: Decide if you want a voicing distinction

Note: Focus on the stops and fricatives as you make this decision.

Tip: If you only want select voicing distinctions within a row of sounds, give them to the alveolars.

Work focus: Organize/Plan/Structure

On the IPA consonant chart, sounds are distinguished by their voicing quality. Voiced consonants are produced with a vibration in the air flow as it passes through your glottis, which you can feel if you place your fingers on the front of your neck while holding out a “zzzzz” sound. (Just make sure you say the sound out loud without whispering it!) Voiceless consonants do not have that vibration, which you can feel if you shift to a sustained “sssss” sound as you touch your neck. Specifically, the rows of stops (or plosives) and fricatives have two entries for most boxes, where the sound on the left is voiceless and the ones on the right are voiced. (The majority of other consonant sounds are voiced.)

Focusing on the stops and fricatives that belong to the columns you selected to keep as options in yesterday’s prompt, decide whether you want your language to meaningfully differentiate among the voiced and voiceless counterparts. That is, do you want a unit like “ba” to carry a completely different meaning from “pa”? Not having a voicing distinction doesn’t mean your speakers can’t produce the different sounds or perceive them differently when they hear them. It just means that the difference is not a meaningful one for your language, so whether a speaker says “ba” or “pa,” the meaning will be the same.

If you decide not to have a voicing distinction, a good option is to only have the voiceless stops and fricatives. (Those voiceless consonants will provide maximal acoustic distinctions from other sounds in the language, making it easier for those sounds to stand out and be differentiated in context.) You can make this decision across the board and choose to remove all voiced stops and/or all voiced fricatives from your inventory.

However, if you want some variation across the sounds, you can choose to keep the distinction at some placements but not others. If you do that, the alveolar sounds, which tend to be the most diverse (and bountiful) across languages, are a good place to have a distinction not made at other places of articulation. That could, for instance, leave you with a series of fricatives like “f, s, z, x,” where the only voiced fricative in the proto-form of your language is an alveolar one.

Once you make your decision about the voicing distinctions, look at the current state of your consonant inventory. I encourage conlangers (especially beginning conlangers) to begin with a consonant inventory that is more moderately sized with somewhere around 12-20 consonant sounds. That guideline is, by no means, a strict one. It’s more of a range to aim for as you consider what sounds to keep. Having too many starting consonant sounds can result in issues later on, where you may forget to actually use all the sounds when creating roots for your language (or where you realize that you’ve created 500 words, but only one of them uses a particular sound). Having too few sounds can lead a conlanger feeling a bit of boredom or repetition as they create new words for their language (i.e. everything ends up feeling the same or sounding the same, making the vocabulary creation a little less fun for some people).

Re-examine your starting consonant inventory and decide if you want to adjust it, taking out more series of sounds or removing individual sounds from within a series (e.g. removing the velar fricative [x] while retaining the velar stop [k]). In general, it’s good to keep a more “balanced” inventory, where the consonants you incorporate tend to reflect a general pattern of having more than one sound produced at a given placement (i.e. most columns will include more than one sound), the alveolar ridge being the “central” grouping of sounds with more diversity of manners of articulation, and stops and fricatives having the most placement options out of all the manners.