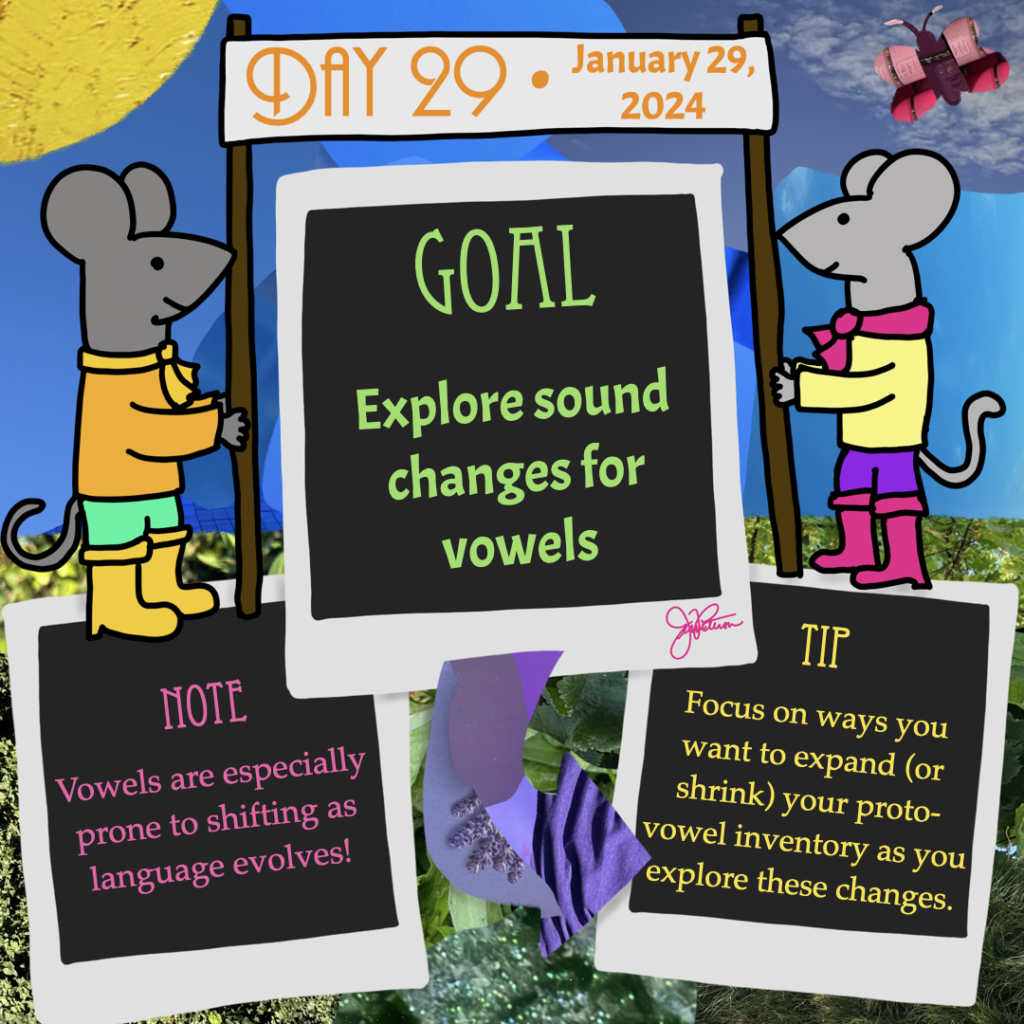

Goal: Explore sound changes for vowels

Note: Vowels are especially prone to shifting as languages evolve.

Tip: Focus on ways you want to expand (or shrink) your proto-vowel inventory as you explore these changes.

Work focus: Learn/Brainstorm/Try

I’ve mentioned a sound change that could affect the vowel—namely that sometimes when coda consonants are deleted, a compensatory feature affects the vowel of the syllable, such as a nasal coda consonant being deleted and leaving behind a nasal vowel (e.g. *bem becomes bẽ). However, some sound changes affect vowels without affecting the consonants surrounding them.

Vowels can shift qualities, especially when there is a coda consonant. For instance, you could consider changes such as the following:

(example a) High vowels lower before nasal codas, so *kin becomes ken, and *lum becomes lom.

(example b) Tense mid-vowels become lax when there is a coda consonant, so *sed becomes [sɛd].

If you had any diphthongs in the proto-stages of your language (or introduced sound changes that removed consonants and, thus, made diphthongs possible), you could also consider introducing sound changes that reduce those diphthongs, such as this example sound change:

(example c) The diphthongs *ai and *au become e and o, respectively. Therefore, *mai becomes me, and *daun becomes don.

There are so many possibilities for shifting diphthongs and reducing them, so if you’re interested in that route, you might look up what has happened in other languages to get some inspiration for all the ways diphthongs can change.

If you had long vowels versus short vowels in your proto-forms (or if you end up introducing a vowel length distinction through other sound changes), you can also decide whether you want sound changes to affect vowels of different temporal lengths differently. In English, one sound change that occurred historically was that long vowels raised (and high long vowels became diphthongs)—but these particular changes only affected the long vowels, and not the short vowels. So, for instance, [geːs] became [gis] “geese” and [iːs] became [ais] “ice” while [is] with its short vowel became the modern “is”.

Another way to get inspiration for new changes is to try saying the forms really quickly, over and over again, to see how you naturally begin to shift the way it is produced. You can try to capture that natural shift in your sound changes to reflect the way you say the forms.